| Return to Misty Moorings - Dispatch V2 |

Northern Connections Trilogy

(Click on Plan to Enlarge for Printing) Dispatch Setup

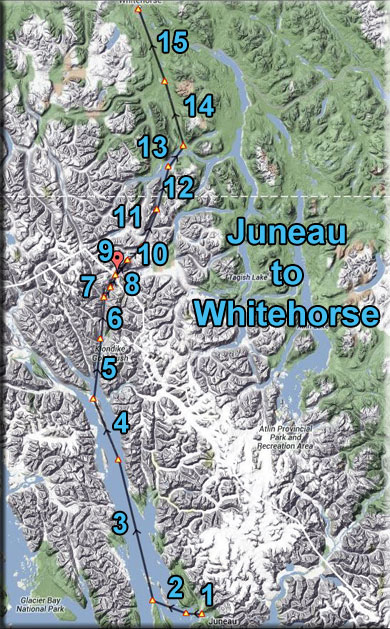

Dispatch Overview Return to Misty Moorings (RTMM) now covers a far larger area with the new software area additions. The "Northern Collections Trilogy" dispatches connect all three areas. Part I is a route from Ketchikan (PAKT) to Juneau (PAJN). Part II is a route from Juneau to Whitehorse (CYXY). Part III is a route from Whitehorse to Wasilla (PAWS). This dispatch is for Part II of the Northern Connections Trilogy. The route takes you from Juneau International (PAJN) to Whitehorse, Yukon, Canada (CYXY). This is the "Gold Rush" leg of the Trilogy since it flies over much of the famous Alaska Gold Rush area. Some of that history and narrative are included in this dispatch. The area covered now by RTMM is literally "vast." Flying "The Northern Connection Dispatches" gives the SIM pilot a far better understanding of the size of the territory and the amazing differences in topography. Flying all three of the "Northern Connections" routes will give you a far better understanding of the Land beneath the wings of the RTMM SIM pilot. NOTAM: This is an "flight-seeing-friendly" flight plan. As long as you control the altitude as listed on each leg of the Trip Ticket, the aircraft will perfectly fly the route so you can sit back and enjoy the amazing view. Leg #01: Juneau Int'l to Coghlan Island NDB (CGL) Comments: Fly the Runway heading (245*) to Coghlan Island. Be sure your altitude is at 1200 feet (adjust the barometer for the weather). Leg #02: Coghlan Island to Point Retreat Lighthouse Comments: Our next way point is the Point Retreat Lighthouse. ORBX SAK has done a beautiful rendition of the lighthouse, fly low over it to see it more closely.

Point Retreat Lighthouse is situated at the northern tip of ninety-mile-long Admiralty Island, which is bordered by Stephens Passage on the east and Chatham Strait on the west. Thousands of tourists view the lighthouse each year from the comfort of cruise ships that call at nearby ports during the temperate summer months but few visitors actually set foot on expansive Admiralty Island as it is home to only one permanent settlement, the tiny Tlingit village of Angoon. The natives call their island Kootznahoo, meaning “Bear Fortress,” and the Alaskan brown bears do seemingly rule the island, outnumbering humans by a ratio of 2:1. Given its prominent position along the Inside Passage, Point Retreat was set aside as a 1,505-acre lighthouse reserve in 1901 by executive order of President McKinley. The point, however, had to wait a couple of years for its lighthouse due to inadequate funding. When the Point Retreat Lighthouse was finally lit on September 15, 1904, it became the tenth light station to be constructed by the U.S. Government in the Alaskan Territory. The first Point Retreat Lighthouse was a six-foot-tall hexagonal wooden tower, topped by a hexagonal lantern room. Two one-and-one-half-story frame dwellings were constructed fifty feet south of the light, but one of them apparently burned down not long after it was completed. The station’s boat, stored in a rectangular boathouse just east of the dwellings, allowed the keepers to make an occasional trip to Juneau. Just before World War I, Point Retreat was stripped of its personnel and downgraded to a minor light. Life, however, returned to the station just a few years later, when a new combination lighthouse and fog signal was built in 1923-24. A one-story, rectangular (30’ x 40’) building housed the fog signal equipment, and from the center of this cement structure a spiral staircase led up to a square tower, which was topped by a circular lantern room. Two new keeper’s dwellings, a landing wharf, derrick, hoist, boathouse, and cisterns were also built at the same time for a total price of $58,242. One of the new station's first keepers was Charles E. McLeod, who sailed from Scotland to New York as a young boy. By 1920, Charles had found his way to Alaska where he served aboard a lightship and worked with a construction crew building lighthouses. On a return visit to Scotland in 1924, he met and married his wife, and then returned to his job in Alaska, telling his wife that he would send for her after his work on the Point Retreat Lighthouse was finished. In 1925, Charles Jr. was born in Glasgow. The following year, the infant and his mother made the lengthy trip to Juneau and then sailed out to Point Retreat where Charles Sr. had hired on as keeper after the construction work was finished. When Charles Jr. was just two, his mother set him on the station's dock railing while she changed the film in her Kodak box camera. While she was distracted, Charles fell forty feet from the dock to the rocks below. Charles Jr. seemed to have suffered little from the fall until a while later when his legs started to bother him. He was taken to Juneau, where he had the misfortune of being treated by a doctor whose inept handling of his injuries left him crippled for life. The station’s small launch used for transportation between Point Retreat and Auke Bay was named Hard Luck Charlie after the boy. Charles Sr. soon had his share of bad luck too, as he developed pneumonia in 1930 and passed away. With the increase of commercial flights to Alaska, airlines launched an intensive campaign for aeronautical beacons to be placed along the Alaskan coastline. Rather than add a second beacon on Admiralty Island, the lantern room from the Point Retreat Lighthouse was simply removed in the 1950’s and replaced by an eight-foot-tall concrete block supporting a double-ended airways beacon. In this manner, the Point Retreat lighthouse could serve both captains and pilots. As the station moved towards automation, one of the two keeper’s dwellings was torn down in 1966 to make room for a helicopter landing pad. Then, in 1973, the station was downgraded to a minor light, and the remaining personnel were removed. The lone dwelling stood vacant and the station received only an occasional checkup visit from the Coast Guard until a 30-year lease on the property was granted to the Alaska Lighthouse Association in 1997. Five years later, the same group received outright ownership of the buildings and the entire 1,505-acres originally set aside for the station. Several groups tried to block the land transfer, feeling that only ten acres should be awarded with the lighthouse. The Alaska Lighthouse Associations plans to use the property to house a maritime museum and a small bed-and-breakfast. Stipulations in the transfer require that the property be accessible to the public. In 2002, all the structures at Point Retreat received a fresh coast of paint, but the station seemed incomplete without the lantern room that was removed decades earlier. A search for the missing lantern room was unsuccessful so Seidelhuber Iron and Bronze works of Seattle was contracted to build a steel replica using architectural drawings found in the National Archives. The new lantern room was installed atop the lighthouse in 2004, just in time for the centennial of the station. The Point Retreat Lighthouse is now fit to start another century of service complete with short-term "keepers" residing in the dwelling. Leg #03: Point Retreat Light to Eldred Rock Lighthouse Comments: We fly up the Lynn Channel to another lighthouse, the Eldred Rock Lighthouse. The Lynn Channel - Lynn Canal is an inlet (not an artificial canal) into the mainland of southeast Alaska. The Lynn Canal runs about 90 miles (140 km) from the inlets of the Chilkat River south to Chatham Strait and Stephens Passage. At over 2,000 feet (610 m) in depth, Lynn Canal is the deepest fjord in North America and one of the deepest and longest in the world as well. The northern portion of the canal braids into the respective Chilkat, Chilkoot, and Taiya Inlets. The Lynn Canal was explored by Joseph Whidbey in 1794 and named by George Vancouver for his birthplace, King's Lynn, Norfolk, England. Lynn Canal's location as a penetrating waterway into the interior connects Skagway and Haines, Alaska to Juneau and the rest of the Inside Passage thus making it a major route for shipping, cruise ships, and ferries. During the Klondike Gold Rush it was a major route to the boom towns of Skagway and Dyea and thence to the Klondike gold fields. The worst maritime disaster in the history of the Pacific Northwest occurred in Lynn Canal during October 1918, when the S.S. Princess Sophia, steaming southbound from Skagway, grounded on the Vanderbilt Reef and later sank, with the loss of all 343 passengers and crew. After the gold rush and the creation of the White Pass and Yukon Route railroad ore and other freight from the Yukon Territory was transported on the railroad to Skagway and its deepwater port and then shipped through Lynn Canal. However, in the 1970s and 1980s the freight subsided as mining activity curtailed in the interior and today very little freight is actually shipped in the Lynn Canal. Currently, transportation in the canal is provided by Alaska Marine Highway ferries. There are also several other entrepreneurial water taxis and ferries available, but the AMHS is far and away the most frequently used. A project of uncertain future is the Lynn Canal Highway. Because of its high use, the Coast Guard installed several lighthouses in the early 20th century including Eldred Rock Light, Sentinel Island Light, and Point Sherman Light. Historically, Lynn Canal proved to be a waterway involved in a dispute of the "Alaskan Panhandle," a strip of land running down the pacific coast between British Columbia and Alaska. Of particular value was the fact that Lynn Canal provided access to the Yukon, where gold was found in 1896. The dispute was fought between Canada and The United States of America, and finally settled in 1903 with the British, weary from fighting in the Boer War, ruled that the Canal was part of Alaska, not British Columbia.

Eldred Rock Lighthouse - Hurricane winds, estimated at ninety miles per hour, were howling down narrow Lynn Canal as the Clara Nevada started her multi-day journey from Skagway to Seattle. It was February 5th, 1898, near the peak of the Alaskan gold rush, and the three-masted passenger ship was loaded with over 800 pounds of the prized mineral, an illegal shipment of dynamite, and some one hundred passengers, including more than one frustrated fortune seeker. Just over thirty miles into her southward voyage, the ship ran aground at Eldred Rock and exploded into flames. The remains of the Clara Nevada are now a popular dive site, but oddly no trace of gold has ever been discovered in the wreckage. According to the initial report, all passengers and crew members on board the vessel that evening perished. However, weeks after the accident, a skiff belonging to the ship was found hidden in a grove of trees on the mainland. A few members of the crew likely escaped the disaster that night, as it was later discovered that C. H. Lewis, captain of the Clara Nevada, had resumed his profession on riverboats in Alaska’s interior and that the ship’s fireman was subsequently employed in Nome’s gold fields. Whether the loss of the Clara Nevada was an accident or an act of sabotage may never be known, but Congress viewed the incident as sufficient evidence that a lighthouse on Eldred Rock was needed. The Lighthouse Board approved plans for the lighthouse in May 1905 and hoped that hired labor could have the design completed before November and the coming of harsh winter weather. Mother nature, however, did not cooperate, and the lighthouse was not activated until June 1, 1906, making it the last of the ten lighthouses constructed in Alaska between 1902 and 1906. Like many of the early northern lights, the Eldred Rock Lighthouse consisted of an octagonal tower protruding from the center of an octagonal building with a sloping roof. The building at Eldred Rock, however, was markedly larger than the others and had two stories instead of one. The bottom story was built of concrete, while the second story and tower were wood. Perhaps it was this solid foundation that has allowed the Eldred Rock Lighthouse to survive for over a hundred years, while all of its Alaskan contemporaries were replaced with stouter structures after just a few decades of service. The lighthouse provided ample living space for the keepers as well as a noisy neighbor, a first class fog signal. A wooden boathouse and tramway were also part of the 2.4-acre lighthouse reservation and were built just north of the lighthouse. A fourth-order Fresnel lens was placed in the lantern room, near the top of the fifty-six foot lighthouse, at a focal plane of ninety-one feet. This unique lens, crafted in Paris by Barbier, Benard & Turenne, consists of two bull’s-eye panels – one about four feet in diameter and the opposing one a smaller, 14-inch panel. A sheet of red glass was placed between the light source and the larger prism, causing the revolving lens to produce alternating red and white flashes. On May 14, 1906, a letter was sent from the office of the district inspector to Nils Peter Adamson, assistant keeper of the Desdamona Sands Lighthouse on the Columbia River, directing him “to proceed to Eldred Rock, Alaska, Light Station and take charge of that station as Keeper.” Adamson was ordered to make no unnecessary delay as the light and fog signal were scheduled to begin operation in just over two weeks. Head Keeper Adamson reached the station in time, and with his two assistants took up residence on the tiny island. On the evening of March 12, 1908, a violent gale struck Eldred Rock. When assistant keeper Currie ventured out of the lighthouse the next morning, to his astonishment he saw a ship stranded on the northern end of the island. The powerful storm had brought the Clara Nevada up from her watery grave, just days after the tenth anniversary of her sinking. Keeper Currie didn’t have much time to examine the resurrected vessel for the storm picked up again that evening, returning the ship to the bottom of the canal. Leg #04: Eldred Rock Lighthouse to Haines NDB (HNS) Comments: ... You will be approaching a peninsula that comes from Haines out into the middle of the Lynn. You must be at 1900 feet as you cross over this. Look closely as you pass over it, there are several communities nestled along both shorelines. Haines was named in honor of Francina Haines of the Presbyterian Home Missions Board. Accompanied by his friend, John Muir, S. Hall Young, was the first missionary to the area in 1879. The purpose of their trip was to scout a location for a mission and a school. The first known meeting between white men and Tlingit took place in 1741 when a Russian ship anchored near Haines and started the fur trade in the area. In 1892, Jack Dalton established a toll road on the Tlingit trade route into the interior to cash in on gold-seekers and others heading north into Canada. Parts of the Dalton Trail are now the Haines Highway. In 1902, ongoing border disputes between the U.S. and Canada provided the justification for an army post in Alaska. The white buildings of Fort William H. Seward still stand and are a distinctive landmark of Haines. Decommissioned in 1947, the fort was bought by a group of war veterans with hopes of creating an arts and commerce community. The buildings are now privately owned homes, accommodations, restaurants, galleries, and shops. The Klondike Gold Rush - The Klondike Gold Rush, also called the Yukon Gold Rush, the Alaska Gold Rush, the Alaska-Yukon Gold Rush and the Last Great Gold Rush, was a migration by an estimated 100,000 prospectors to the Klondike region of the Yukon in north-western Canada between 1896 and 1899. Gold was discovered here on August 16, 1896 and, when news reached Seattle and San Francisco the following year, it triggered a "stampede" of would-be prospectors. The journey proved too hard to many and only between 30,000 and 40,000 managed to arrive. Some became wealthy; however, the majority went in vain and only around 4,000 struck gold. The Klondike Gold Rush ended in 1899 after gold was discovered in Nome, prompting an exodus from the Klondike. It has been immortalized by photographs, books and films. Prospectors had begun to mine gold in the Yukon from the 1880s onwards. When the rich deposits were discovered along the Klondike River in 1896, it was met with great local excitement; however, the remoteness of the region and the extreme winter climate prevented news from reaching the outside world until the following year. A stampede that came to mark the height of the rush began with the arrival of ships bringing gold from Klondike at north-western American ports in July 1897. Newspaper reports of the gold fueled a nation-wide hysteria where many left their jobs and set off for the Klondike as prospectors. These in turn were joined by traders, writers, photographers and others trying to make a profit from them. To reach the gold fields most took the route through the ports of Dyea and Skagway in Southeast Alaska. Here, the Klondikers could follow either the Chilkoot or the White Pass trails to the Yukon River and sail down to the Klondike. Each of them was required to bring a year's supply of food by the Canadian authorities in order to prevent starvation; in all, their equipment weighed close to a ton, which for most had to be carried in stages by themselves. Together with mountainous terrain and cold climate this meant that those who persisted did not arrive until summer 1898. Once there, they found few opportunities and many left disappointed. Mining was challenging, the ore was distributed in a manner that could fool even experienced prospectors and digging was made slow by permafrost. As a result, some miners chose to buy and sell claims, building up huge investments and letting others do the work. To accommodate the prospectors, boom towns sprang up along the routes and at their end Dawson City was founded at the confluence of the Klondike and the Yukon River. From a population of 500 in 1896, the hastily constructed town came to house around 30,000 people by summer 1898. Poorly built, isolated and unsanitary Dawson suffered from fires, high prices and epidemics. Despite this, the wealthiest prospectors spent extravagantly gambling and drinking in the saloons. The Native Hän people, on the other hand, suffered from the rush. Many of them died after being moved into a reserve to make way for the stampeders. From 1898, the newspapers that had encouraged so many to travel to the Klondike lost interest in it. When news arrived in the summer of 1899 that gold had been discovered in Nome in west Alaska, many prospectors left the Klondike for the new gold fields, marking the end of the rush. The boom towns declined and the population of Dawson City fell away. In terms of mining, the gold rush lasted until 1903 when production peaked after heavier equipment was brought in. Since then, the Klondike has been mined on and off and an estimated 1,250,000 pounds (570,000 kg) of gold has been taken from the area. Today the legacy draws tourists to the region and contributes to keeping it alive. Watch for the Davidson Glacier to port as we fly up the Channel. As you end this leg, Haines will be about 10 degrees to port, you can land there if you like, then continue later toward Skagway. Leg #05: Haines NDB to Skagway Turnoff

Comments: If you are going to land at Skagway, you should be decreasing your altitude and be getting ready for a landing. You are now flying up the Taiya Inlet. When you get near the end of the Taiya Inlet, a sharp turn to starboard puts you on the runway at Skagway. If you do not wish to land, maintain 1900 feet altitude. This is a beautiful little community and well worth the time to land and look around. But if you are in a hurry, continue with the gps plan. Skagway - A Historic Gold Rush Town Skagway Today: The Skagway area today is home to the Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park and White Pass and Chilkoot Trails. Skagway has a historic district of about 100 buildings from the gold rush era. It receives about 3/4 million tourists annually, most of whom come on cruise ships. The White Pass and Yukon Route railway still operates its narrow-gauge train around Skagway during the summer months. Skagway is now also served by the Klondike Highway, completed in 1978, which connects it to the Alaska Highway. The White Pass Railroad "docks" right at the cruise ship docks. You can step off the ship and onto the train. It takes you high above Skagway up the historic pass where so many lost their lives during the Gold Rush.

Leg #06: Skagway Turnoff to Nourse River Heading:006* Distance: 1.2 NM Altitude: 1900 - 1900 (unless landing) Comments: We will be flying to the outfall of the Nourse River, up a valley that will lead us to Chilkoot Pass. Leg #07: Nourse River to Dead Man's Trail You must now push the throttle forward and climb steeply. We are going to be flying up the Chilkoot Pass. The first way point on the way is Dead Man's Trail and you should be at 2800 feet passing that way point. Leg #08: Dead Man's Trail to Chilkoot Pass Heading: 358* Distance: 3NM Altitude: 2800 - 4000 (Increase Altitude Sharply) Comments: You are heading up the "deadly" Chilkoot Pass. Another pass, the White Pass, 5 miles to starboard, were the only "routes" to the gold fields. Not only were many human lives lost on the trails going up to this pass, but thousands of animals died trying to carry the loads, and were just pushed off the side of the mountain. The bones are littered all along the trail which is still visible from the train and highway. Climb steeply. Look at the terrain below, imagine men with horses and donkeys fully loaded trying to struggle up this sheer rock climb. Comments:Chilkoot Pass History: Skagway has one of the most colorful histories of any place in Alaska. In 1896, gold was found in the Klondike region of Canada's Yukon Territory. Beginning in the summer of 1897, thousands of hopeful miners poured in to the new town and prepared for the 500-mile journey to the gold fields in Canada. This journey began for many when they climbed the mountains over the White Pass above Skagway and onward across the Canada border to the Lake Bennett, or one of its neighboring lakes, where they built barges and floated down the Yukon River to the gold fields around Dawson City. Others disembarked at nearby Dyea, northwest of Skagway, and crossed northward on the Chilkoot Pass, an existing Tlingit trade route to reach the lakes. Some prospectors also realized how difficult the trek would be that lay ahead on the route and chose to stay behind to supply goods and services to miners. Within a year, stores, saloons, and offices lined the muddy streets of Skagway. The population was estimated at 8,000 residents during the spring of 1898 with approximately 1,000 prospective miners passing through town each week. By June 1898, with a population between 8,000 and 10,000, Skagway was the largest city in Alaska. As you pass over the summit, look carefully and you will see a border control station there. Leg #09: Chilkoot Pass to Long Lake Heading: 015* Distance: 4.5 NM Altitude: 4000 - 4000 (maintain altitude) Comments: Continue to increase your altitude as you fly over Long lake on your way to Lindeman Lake (ahead 5 miles) Leg #10: Long Lake to Lindeman Lake Heading: 022* Distance: 4.6 NM Altitude: 4000 - 3600 (Reduce Altitude) Comments: As you fly over the lake, reduce your altitude to 3600 feet. You will pass over three, Long Lake, Lindeman and Bennett. All three were very important to the "49er's" as you'll learn during the next leg. Leg #11: Lindeman Lake to Bennett Lake Heading: 358* Distance: 9.3 NM Altitude: 3600 - 3400 (Reduce Altitude) Comments: Reduce Altitude to 3400 Feet. This keeps you about 1200 feet above the lakes and terrain. Klondike stampeders set up camp along the shores of Lake Lindeman and Lake Bennett during the winter of 1897-1898. These men, women and children had managed to drag and carry tons of provisions over the harsh trails down to the lakes, which formed the headwaters of the Yukon River. The crowd had to wait for the river ice to break before they could sail down the Yukon into Dawson. Some stampeders stayed at Lake Lindeman, the end of the Chilkoot Pass, many more kept moving down the trail and set up camp at Lake Bennett, which was also the terminus of the White Pass trail. "Knock-down boats of every conceivable sort are being taken up since the reports have come down that boat timber is very scarce, as well as high in price. . . . Reports are discouraging about [carrying] boats. The trails up the mountains are reported so narrow and tortuous that long pieces cannot be carried over. In that case [mine] may never get over. Hundreds of boats, it is said, are left behind." Most stampeders needed to build their own boats, having declined to drag a boat over the pass. The preferred wood cutting technique, known as "whipsawing," led to more than a few disagreements and fights. Logs placed on stands were sawed by one man standing on top of the log with one end of the saw and a second man standing below the log holding the other end. The work was so hard, that no matter which position he took, it was easy to for each man to believe that he was doing all the work. Lake Lindeman was the terminus of the Chilkoot Pass trail. Many stampeders, exhausted after dragging a ton of supplies over the pass, chose to camp by the side of Lake Lindeman to wait out the winter. When one traveler, Julius Price, who crossed the Chilkoot Pass in 1898, first saw the tent city growing up along the shores of Lake Lindeman, he noted that the vast spread of white tents looked "like a flock of seagulls on a distant beach." By the end of September 1897, hundreds of men and women were in Lindeman, busy building boats for the journey down the Yukon. Their numbers grew to over 1,000 by the end of the year. When the Yukon River began to thaw in late May, over 4,000 people were camped out along Lake Lindeman. Mail was critical to stampeder morale during the winter of 1897/1898. Stuck in tents stretched out along Lake Lindeman and Lake Bennett, these thousands of men and women had little to occupy their time and longed for word from home. For a time, U.S. mail was only carried as far north as Sheep Camp, along the Chilkoot Pass trail. Private, unofficial mail carriers made some money ferrying letters between Sheep Camp and the tent lake cities. Lake Bennett was the end of the White Pass trail. Stampeders who had passed over the mountains from Skagway during 1897 spent the winter camped along the lake shore. They were joined by thousands who had crossed over the Chilkoot Pass and continued down to Bennett before stopping to camp, waiting for the spring thaw. The most pressing activity of all who arrived at the tent cities along the lakes was boat building. Few experienced boat builders were among the thousands of clerks, farmers, and workers who crowded the shores along the headwaters of the Yukon. They learned from watching, doing and their own mistakes. At long last, after months of waiting for many, the ice covering the Yukon River began to break up. Rumors about the conditions of the ice flew through the tent cities at Bennett and Lindeman. Some stampeders, thinking that the river was clear, set out too early and got stuck in ice jams. Leg #12: Bennett Lake to Watson Heading: 351* Distance: 10.2 NM Altitude: 3400 - 3400 Comments: When you get to Bennett, you will see a small train station to starboard. This is the White Pass Railroad that comes from Skagway and goes all the way to Whitehorse. We will be following the route of the railroad the rest of the trip.

The White Pass and Yukon Route railroad - Built in 1898 during the Klondike Gold Rush, this narrow gauge railroad is an International Historic Civil Engineering Landmark, a designation shared with the Panama Canal, the Eiffel Tower and the Statue of Liberty. Leg #13: Watson to Carcross Heading: 012* Distance: 6 NM Altitude: 3400 - 3400 Comments: Caribou Crossing was a fishing and hunting camp for Inland Tlingit and Tagish people. 4,500-year-old artifacts from First Nations people living in the area have been found in the region. Caribou Crossing was named after the migration of huge numbers of caribou across the natural land bridge between Lake Bennett and Nares Lake. That caribou herd was decimated during the Klondike Gold Rush, but a recovery program raised the number of animals to about 450. The modern village began in 1896, during the Klondike Gold Rush. At the time, Caribou Crossing was a popular stopping place for prospectors going to and from the gold fields of Dawson City. Caribou Crossing was also a station for the Royal Mail and the Dominion Telegraph Line, and it served as a communications point on the Yukon River. Tour buses at a large tourist stop in Carcross. In 1904, Caribou Crossing was renamed Carcross as a result of some mail mix-ups with the Cariboo Regional District in nearby British Columbia. Silver mining was promoted nearby in Conrad, Yukon in the early 1900s, but there was little to be found and mining efforts soon ended. Mineral exploration continues today, but tourism is far more important to the economy of the community. Leg #14: Carcross to Robinson NDB (PJ) Heading: 320* Distance: 15.3 NM Altitude: 3400 - 3500 (Increase Altitude) Comments: Maintain altitude. This land is flat with no obstacles. The airport is about 20 miles ahead, so you have plenty of time to reduce altitude for landing. Leg #15: Robinson NDB to Whitehorse (CYXY) ILS: IXL, 109.5 Comments: Welcome to Whitehorse! Whitehorse History: Before 1896. Archeological research south of the downtown area, at a location known as Canyon City, has revealed evidence of use by First Nations for several thousand years. The surrounding area had seasonal fish camps and Frederick Schwatka, in 1883, observed the presence of a portage trail used to bypass Miles Canyon. Before the Gold Rush, several different tribes passed through the area seasonally and their territories overlapped. The discovery of gold in the Klondike in August, 1896, by Skookum Jim, Tagish Charlie and George Washington Carmack set off a major change in the historical patterns of the region. Early prospectors used the Chilkoot Pass, but by July 1897, crowds of neophyte stampeders had arrived via steamship and were camping at "White Horse". By June 1898, there was a bottleneck of stampeders at Canyon City, many boats had been lost to the rapids as well as five people. Samuel Steele of the North-West Mounted Police said: "why more casualties have not occurred is a mystery to me." On their way to find gold, stampeders also found copper in the "copper belt" in the hills west of Whitehorse. The first copper claims were staked by Jack McIntyre on July 6, 1898, and Sam McGee on July 16, 1899. Two tram lines were built, one 8 km (5 mi) stretch on the east bank of the river from Canyon City to the rapids, just across from the present day downtown, the other was built on the west bank of the river. A small settlement was developing at Canyon City but the completion of the railway to Whitehorse in 1900 put a halt to it. The White Pass and Yukon Route narrow-gauge railway linking Skagway to Whitehorse had begun construction in May 1898, by May 1899 construction had arrived at the south end of Bennett lake. Construction began again at the north end of Bennett lake to Whitehorse. It was only in June–July 1890 that construction finished the difficult Bennett lake section itself, completing the entire route. By 1901, the Whitehorse Star was already reporting on daily freight volumes. That summer there were four trains per day. Even though traders and prospectors were all calling the city Whitehorse (White Horse), there was an attempt by the railway people to change the name to Closeleigh (British Close brothers provided funding for the railway), this was refused by William Ogilvie, the territory's Commissioner. Whitehorse was booming. In 1920 the first planes landed in Whitehorse and the first air mail was sent in November 1927. Until 1942, river and air were the only way to get to Whitehorse but in 1942 the US military decided an interior road would be safer to transfer troops and provisions between Alaska and the US mainland and began construction of the Alaska Highway. The entire 2,500 km (1,553 mi) project was accomplished between March and November 1942. The Canadian portion of the highway was only returned to Canadian sovereignty after the war. In 1950 the city was incorporated and by 1951, the population had doubled from its 1941 numbers. On April 1, 1953, the city was designated the capital of the Yukon Territory when the seat was moved from Dawson City after the construction of the Klondike Highway. On March 21, 1957, the name was officially changed from White Horse to Whitehorse |